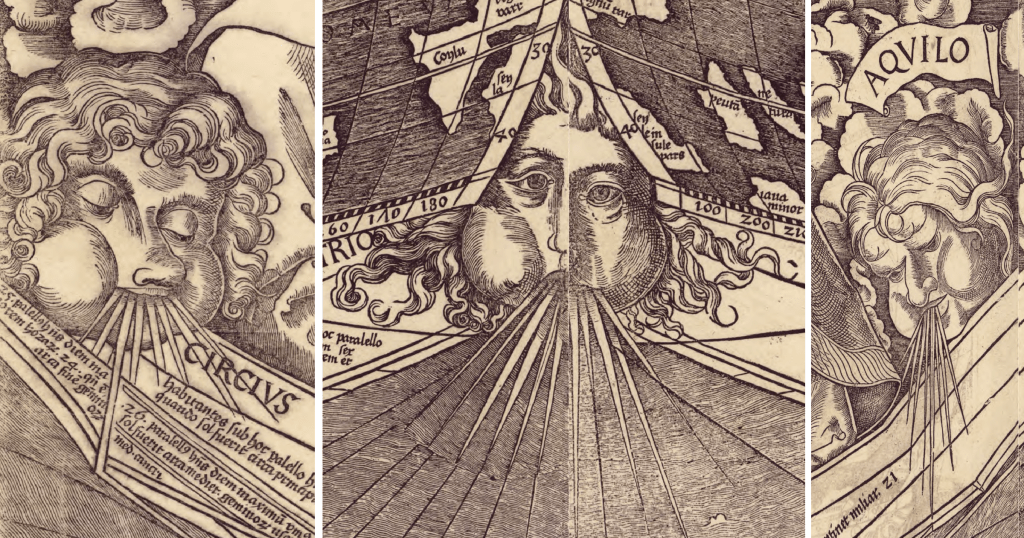

Fig. 4.5. Three Windheads at the Top of Waldseemüller’s Universalis Cosmographia

Details from Martin Waldseemüller, Universalis Cosmographia, 1507, Geography and Map Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

On Waldseemüller’s Universalis Cosmographia the traditional winds encompass the new space of the Atlantic. Ringmann and Waldseemüller devote a whole chapter in the Cosmographiae Introductio to the winds, which suggests that the placement of windheads on the Universalis Cosmographia would have been important to Waldseemüller. Their design and execution seems to have been equally important to the artisans who worked on the huge printed map. We can assume that Waldseemüller insisted that each of the twelve windheads be distinct, (as befitted their known natures), be positioned correctly, and be named in Latin. However, once Waldseemüller had indicated what windhead went where, the drawing and cutting of the windheads fell to the designer and the woodcutter. The artists set each against a background of closely drawn parallel lines–the sky–and billowing clouds. The curved lines with hatching created fat cheeks and pursed lips, while long tapering lines shaped hanks of hair with flowing curls. Above are three windheads Circius, Septentrio, and Aquilo. Circius (see above, left) and Aquilo (see above, right) have curling locks of hair, their cheeks are puffy and full, and careful shading gives their heads and faces depth. Septentrio, emerges from the space where the two hemispheric maps meet at the top of the Universalis Cosmographia–one half of Septentrio falls on the Eastern Hemisphere and the other on The Western (see above, center). Each of the windheads blows wind, symbolized by long thin blades that emerge from its mouth and extend into the map.