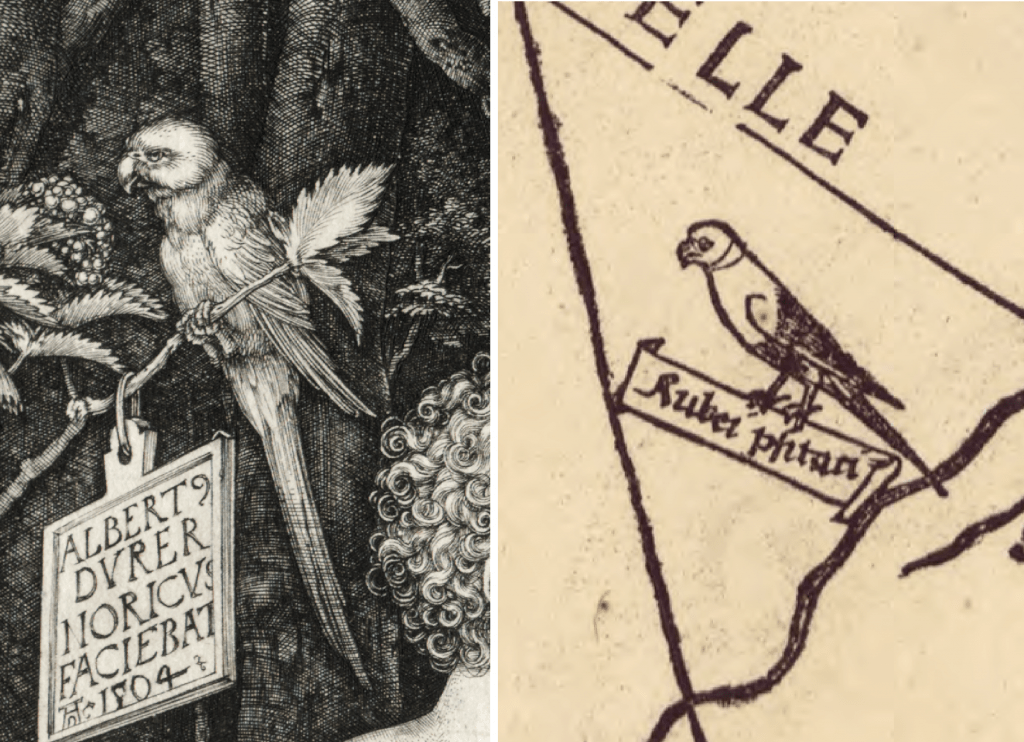

Figure 5.3. Engraved and Woodcut Parrots

Details from Albrecht Dürer, Adam and Eve, 1504, Cleveland Museum of Art (left) and Martin Waldseemüller, Universalis Cosmographia, 1507, Geography and Map Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC (right).

The parrot became simpler as it moved from manuscript chart to printed map, see fig. 5.1. Can the simplification of the parrot be explained by the different media? In other words, is the parrot simpler because it was a woodcut and not a painting? If this is the case, the simplification of the parrot occurred not because of copying, but because the medium of woodblock printing was not sophisticated enough to allow a detailed copy. To answer this question, we must turn to other images of parrots in the medium of print. The artisans designing and cutting the blocks for Waldseemüller’s map were likely familiar with the parrot that appears in Adam and Eve by Albrecht Dürer (above, left). Behind Adam’s head in Adam and Eve, Dürer placed a bird that has been identified both as a macaw and as a ring parakeet. The parrot on Waldseemüller’s world map is strikingly similar but Waldseemüller’s parrot is greatly simplified (above, right).

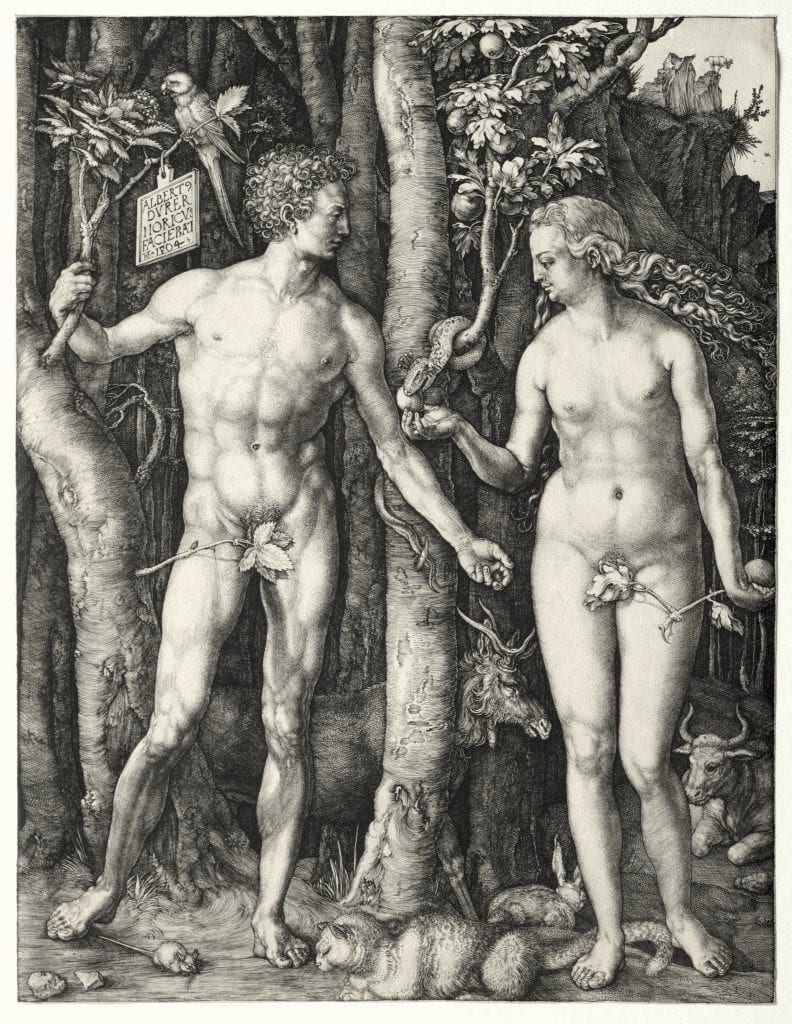

Albrecht Dürer, Adam and Eve, 1504, engraving, Cleveland Museum of Art.

The print media used for these two printed parrots are not the same. Dürer’s Adam and Eve is an intaglio engraving whereas Waldseemülleer’s parrot is a woodblock relief print. Even though both processes result in a piece of paper carrying an inked illustration, the preparation of the base and the printing of the image is different. In intaglio, the copper plate is fairly soft, and the artist uses a tool called a burin, and by varying the pressure can produce thick and thin lines, as well as curves that swell and taper. In the printing process, the ink flows into the crevices made by the burin, the plate is wiped clean, and a high pressure “roller press” forces the ink from the grooves in the copper plate onto the paper. In contrast, in relief printing, the woodcutter cuts away all parts of the wood block intended to remain white on the finished print, and leaves behind ridges that will receive the ink and become black in the final print. The printing press for a woodblock print around 1500 was the same kind of press used for printing books.

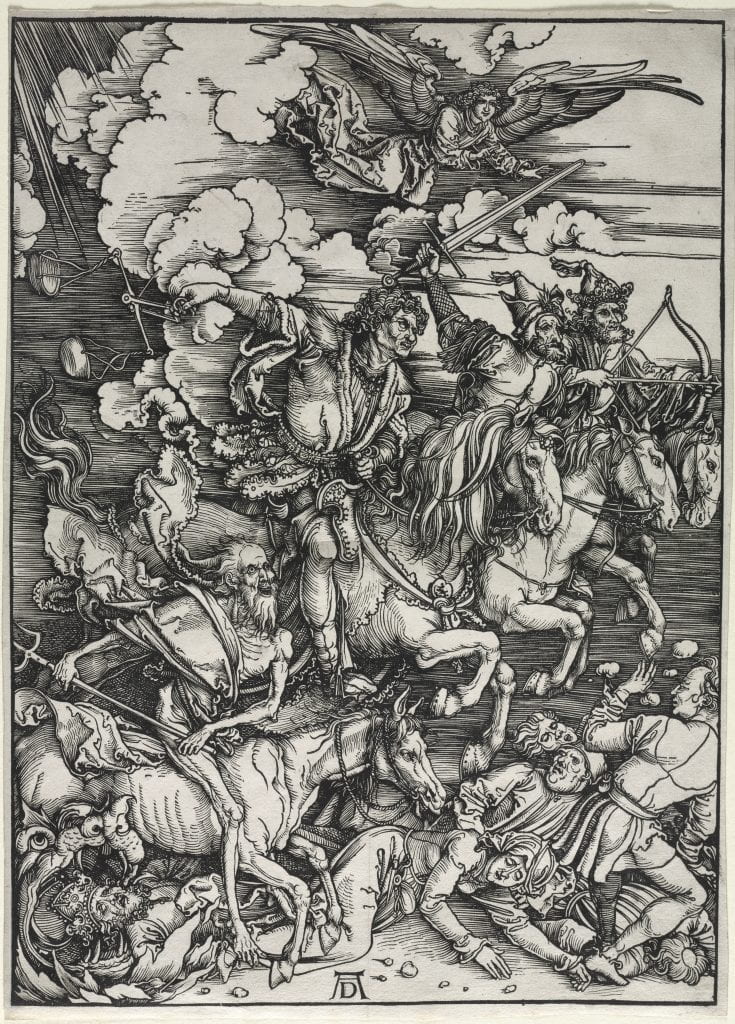

Would the medium of the woodblock print have prevented the creation of a finely detailed image of a parrot that could appear on Waldseemüller’s map? Dürer’s woodcuts that predate the Universalis Cosmographia suggest the answer is yes. It would have been possible to capture the detail in a woodblock relief print. The woodcuts of Dürer’s Apocalypse series (see below), display careful attention to detail and exhibit a range of textures. By 1500, woodcutting was so well developed in Germany that a skilled woodcutter could have reproduced a more detailed bird on Waldseemüller’s map. The medium would have allowed it, but apparently, it was not deemed important to do so.

Albrecht Dürer, The Four Horsemen, from The Apocalypse, 1498, woodcut, Cleveland Museum of Art.